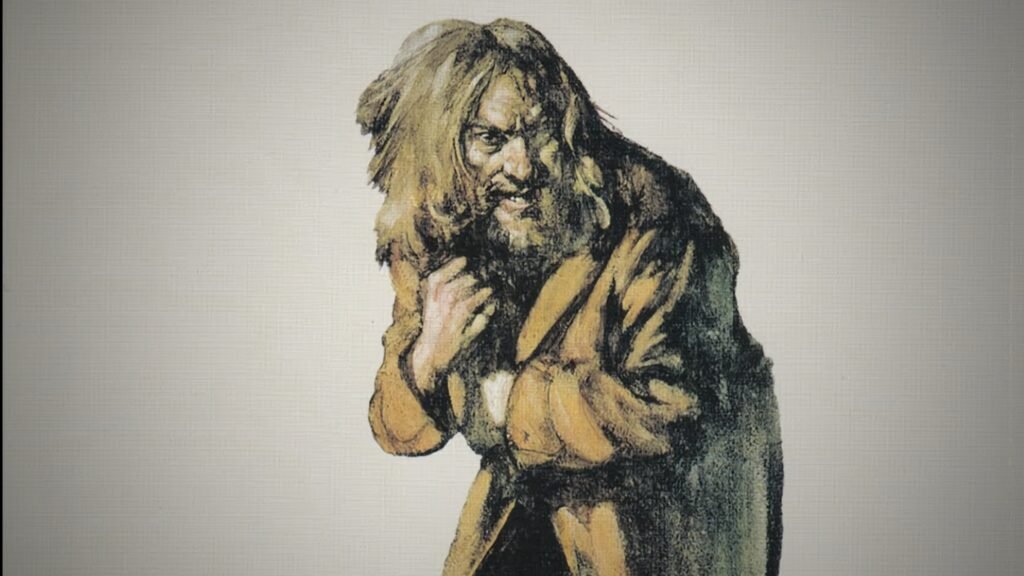

Going through an old archive, I rediscovered this terrific article on Burton Silverman, best known (to his chagrin) as the painter of the cover art to Jethro Tull’s Aqualung. Here’s an age-old story — an artist does an inexpensive, flat-fee work-for-hire. And then the product takes off and earns millions for everyone except that artist. From the article:

The tale of how Chrysalis Records had done him wrong was turned into somewhat of a running family gag. Given the haggard figure he created, we mused that he might eventually embody his own artistic creation — a destitute, howling figure draped in rags and huddled in a darkened street corner. Buried within this bit of gallows humor lies a nagging truth: There’s a palpable sense of unease and frustration at seeing something he created become immensely popular — define his career, even — only to see his ownership of the work taken away, thanks in no small part to the persistent myths and outright falsehoods that have been told about the artistic inspiration for the cover.

The ‘persistent myths and outright falsehoods’ refers to how Ian Anderson, leader of Jethro Tull, keeps telling everyone that the figure on the cover is a representation of him. Silverman insists it’s not, and one wonders if he’d care so much if Anderson wasn’t such a knucklehead about this.1I believe Silverman here — the article is convincing — but, tbh, it does look a little like Anderson.

Silverman is a successful enough artist — recipient of countless awards and permanent collection inclusions — that his Wikipedia entry barely mentions his association with Jethro Tull. So, it’s not like Silverman owes his success to the band. But it grates on him. Silverman’s handshake agreement with Chrysalis didn’t anticipate all the t-shirts, the merchandise, the dorm room posters, and Anderson claiming ownership because he believes he’s the scary cover dude. (Anderson has also annoyed Silverman by publicly referring to the cover as “messy” and “not very attractive or well executed.”)

There’s no contract, an error on Silverman’s part, so maybe he doesn’t have a right to complain. Legally this is a grey area, detailed by a copyright attorney in the article.

I recall other work-for-hire arrangements where there was a cut-and-dry contract, the project takes off, and the artist feels cheated. In particular, there’s one producer who did a remix of a known ’80s song.2It’s not essential to this story to name names. The remix took off, becoming a top-charting hit in the UK. The producer signed a ‘flat-fee’ agreement — no one forced him — but he felt the label should pay him royalties.

The remixer started publicly complaining that he wasn’t paid enough and should be entitled to a cut of the song royalty. “My remix is why this is popular,” he reasoned. He brought this up in every interview and article that featured him, perhaps oblivious that this remix of someone else’s popular song was the only reason for the interview.

In other words, rather than adopting a ‘body of work’ mindset and building on the success of this project, the producer was publicly renegotiating an arrangement that wasn’t negotiable.

A couple of labels commissioned the producer for other high profile remixes over the next several months, but nothing else was a hit. He disappeared from the charts and public interest shortly afterward. I am sure many in the industry passed on working with this producer because of his attitude and public airing of ‘sour grapes.’

Seth Godin writes about situations like this in a 2018 blog post titled Considering the Buyout. He brings up the “I Love NY” logo, which Milton Glaser designed for $2000, and the Nike swoosh, designed by Carolyn Davidson for an astonishing $35. Godin refers to these projects, and the remix and album cover above, as illustration, not art. They might be artistic — especially in Silverman’s case — but, Godin says, “Illustration has a client … taking on all the risk. The artist is free to wander, and free to own the consequences.” He continues:

As Milton Glaser has shown, being associated with dramatic success as an illustrator opens the door to even more success. It can fuel your art and create opportunities for higher leverage in your illustration work as well. Illustration can pay some bills at the same time it chips away at your obscurity problem.

Derek Sivers talks about how if your answer isn’t an enthusiastic “hell, yes!” then it should be a definite “no.” But, he adds a caveat: when you’re starting out and building leverage, then often a “yes” will do. “Hell, yes!” is for artists with leverage, and it might take a few frustrating work-for-hire ‘yeses’ to finally exercise that privilege.

🔗→ My Dad Painted the Iconic Cover for Jethro Tull’s ‘Aqualung,’ and It’s Haunted Him Ever Since

🔗→ Considering the Buyout