I’m thinking a lot about how listening creates spaces, both shared and solitary. In the Strange Times, with no concerts and shuttered venues, you might think isolated listening is the only game in town. But, unexpectedly, live-streaming is opening up new opportunities for a shared listening experience, and I’m not talking about the facsimile of hanging out with distant Zoom-mates.

If there’s one thing live-streaming is bringing back, it’s shared listening in our homes. I thought about this last Thursday when I caught Rishi from Elephant Stone live-streaming from his basement. As I listened, I scrolled through the top bar in Zoom, checking out the other attendees. Many had their kids, family, and friends enjoying the stream with them. Eventually, Caroline joined me in our video square, snow-white cat in tow, and we listened together as Rishi rocked out on sitar.

I know we still (sometimes) watch television shows together, but we’re focused on the music in this case. The video might draw us in, but upon our arrival, the image is an afterthought. We’re silently listening, paying attention to sound, occasionally breaking the spell to comment in the ‘chat’ stream on what we’re hearing. In a way, it’s a replication of meeting at a nightclub (though a coffeehouse is more apt) but only with our family and closest friends.

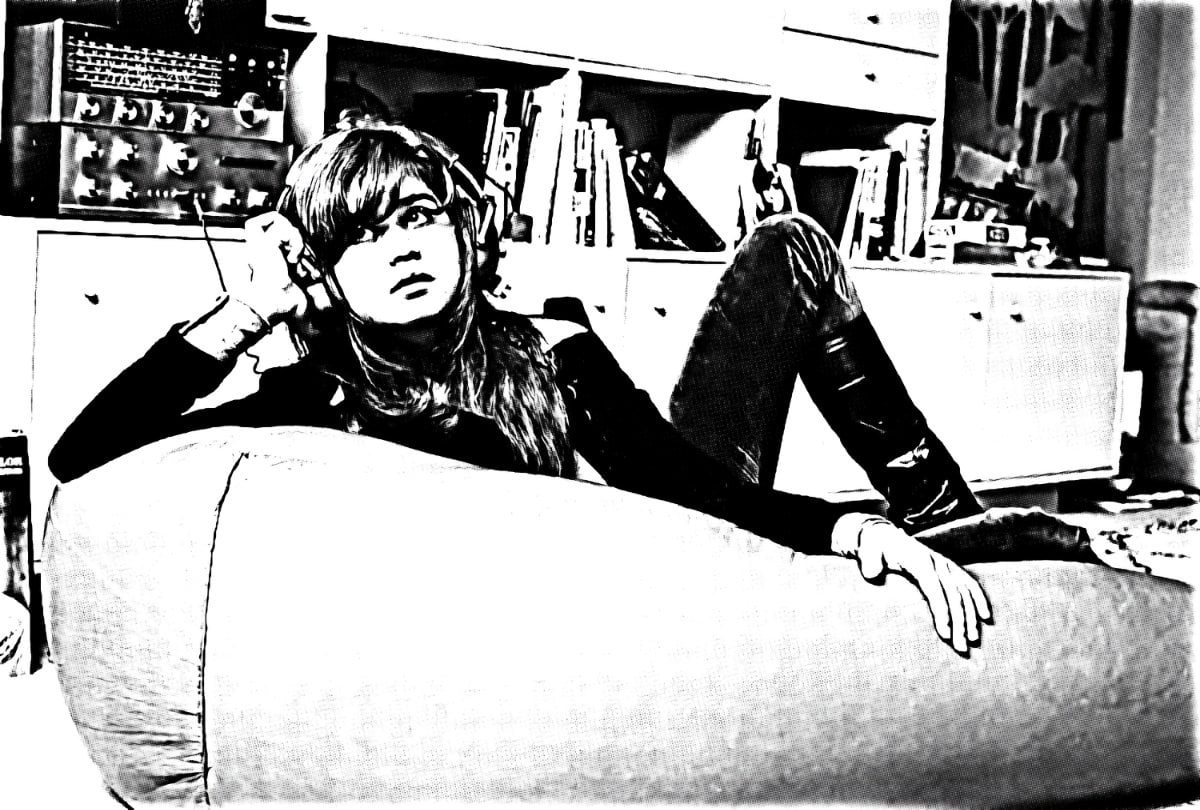

We’ve all seen those vintage photos of the family crowded around the radio, presumably listening to audio theater — but sometimes it’s music that’s holding their attention. And in pictures from the ’50s and ’60s, we see a gathering of teenagers, one placing the record on the turntable while the others gaze at the album cover or dance around the bedroom. Listening was only private if no one else was around. One could wear headphones (now appearing comically oversized), but there was no mobility. Headphone listening could pass for teenage rebellion if the family were also in the room, but mostly it was awkward.

The transistor radio — and, to a degree, the car radio — allowed the music to travel as the immediate surroundings changed. This movement created the first personal soundtrack, though other people could pop in and out of our movie (in the licensing world, the phrase ‘interstitial music’ refers to music that all the characters in a scene can hear). Then, of course, the cassette and the Walkman added a new way to listen — a genuinely private listening experience. We choose the music, and we choose where we want to go with it. The combination puts us inside the movie, shifting the soundtrack to our inner lives.

The Walkman (briefly called the Soundabout) debuted in most places outside of Japan in 1980. The early versions were bulky and — in a misunderstanding of how the device would change listening — came with an extra headphone port for a friend. A button paused the music and activated a microphone so the paired listeners could talk to each other. Sony jettisoned these features once it was clear users preferred to listen on their own in sonic isolation.

In a way, the Walkman and its successors aren’t too different from a psychedelic device, like an audio Dream Machine, altering a state of awareness and heightening perceptions of the moment. Music production had already gotten trippy thanks to a chemically-enhanced counter-culture and studio-as-instrument innovations. Once the music appeared in the middle of one’s head with a wider-than-wide stereo field, things got extra-groovy. As we wander about, the brain’s penchant for connecting images with sound adds meaning and color to the more expansive music.

In the academic paper Make a Sound Garden Grow: Exploring the New Media Potential of Social Soundscaping, the authors cite a 1993 quote from writer William Gibson: “The Sony Walkman has done more to change human perception than any virtual reality gadget. I can’t remember any technological experience since that was quite so wonderful at being able to take music and move it through landscapes and architecture.” The paper continues:

As William Gibson suggests, the Walkman was a revolutionary technology when it was released in 1979 that allowed people to impart a personalized soundtrack over shared public spaces. The Walkman was a significant departure from another popular mobile technology of the time: the boom box. The boom box made private tastes public by merging the music one listened to with the shared sounds of a public space. The Walkman, on the other hand, made possible a more private form of listening.

——————

I remember a time in New York City in the mid-90s. I was walking the avenues with a friend who made especially jarring sheets-of-layered-noise slow techno. He handed me the headphones to his Walkman so I could check out a new track. The music began filling my head with all these textures and brutal sound blasts. Then we turned a corner, and suddenly we were at the edge of a crime scene — yellow tape everywhere, smoke hugging the pavement, men in dark uniforms excitedly talking on radios. I wasn’t sure if we were supposed to be there — it seemed dangerous. And the music instantly became a part of everything around. It was the glue combining the whole of my perception at that moment. We passed the scene right as the track ended. I took the headphones off, looked at my friend, and said something like, “whoa.” Twenty-five years later, that’s still one of my most potent and memorable music moments.

——————

Walkman-adjacent means of listening — today’s earbud activities — seem ideally suited for social distancing. Amanda Petrusich, writing about the approaching ubiquity of headphones four years ago, predicted:

It seems possible, though, that we are slowly reconfiguring music as a private pleasure—that, in fact, all pleasures, soon, may be private. We are all the lone stars of secret films, narrated by and in our own minds, and we seek out music that validates that position: separate, but forever plugged in.

That may have been our trajectory. And beyond facilitating an intentionally isolated experience, earbuds acted as a stay-six-feet-away signal. In co-working spaces, I used headphones to imply, ‘I’m hard at work.’ The seat next to me often remained empty. Headphones on walkers, joggers, and public-transported commuters keep the inquisitive, bothersome, or flirtatious at bay. Headphones became an extension of ‘the bubble,’ a signifier of our personal space.

I know that we’re often not walking around with headphones in our homes — though I occasionally do, don’t judge — but one might think social distancing signals the apex of private listening. But we could have easily anticipated the need to experience things together once again. Staying home for months accentuates the lack of concerts or nightclubs or even a chance encounter with a great song in a retail shop or through the window of a passing car. I don’t know about you, but I’ve found myself listening to — and commenting on — music with family, partners, and friends in my ‘social pod’ more than before. I’m not talking about interacting with music through things like Tim’s Twitter Listening Party. That’s fun and fabulous and, yes, another form of shared listening that feels kinda radical. Besides Twitter parties, I feel like we’re starting to listen together again, live, and in person. I admit the concept is subtle, and you might not notice that it’s happening. And it’s not just through enjoying live-streams together. Our lockdown-inspired shared listening feels new, distant from that family engrossed in radio theater, but operating in a similar momentary environment.

——————

The music critic Amanda Petrusich, who I mentioned above, also thinks a lot about the spaces we create by how we listen. Back in 2010, she was interviewed for NPR under the Get To Know A Critic banner. The correspondent asked, “What’s your ideal way to listen to a record?”

… it’s true — some music is easier to type to, and some music rewards repeat listens in different ways. My knee-jerk tendency is to want to listen to music on vinyl, through headphones (no earbuds, never earbuds), all alone, with the lights turned off (in other words, the way I listened to music when I was fifteen), but I fight that whenever possible, because it’s really not fair. Music doesn’t function that way; it needs to breathe.

If I’m stuck on a record review, I’ll put something on my iPod and ride around on the subway for an hour, listening on my headphones. I think almost all music sounds better on the subway or in a moving car with the windows rolled down. Or I’ll go for a run with it — there’s no better way to get inside the rhythm section of a song than by running to it. It’s not always practical to implement, but I do at least try to think about where and when something was meant to be heard.

I like the idea of thinking not only about why we listen, but also where and how. We’ve all got favorite songs for specific environments and situations — playlists we make for driving or studying reflect this. But it’s also useful to think about how listening technologies affect one’s perception of songs, whether its headphones or shared speakers or a platform like Spotify. Inevitably these combinations color music and invite context. Deep listening (which I’ve talked about before) requires intentionally tuning these variants, increasing opportunities for meaning and connection. However, surprises that fuse with an unintended soundtrack — like my NYC crime scene episode — can offer the most powerful associations.

This post was adapted from Ringo Dreams of Lawn Care, a weekly newsletter loosely about music-making, music-listening, and how technology changes the culture around those things. Click here to check out the latest issue and subscribe.