Musical collisions can create the most exciting and innovative sounds. I’m fascinated by that gray space on the Venn diagram between two disparate genres, instruments, or creative objectives. Jon Hassell combined elements of ancient world music with electronics and spawned a blurred terrain he termed ‘fourth world music.’ And I’ve written previously about the fun things that happened when classic rockers ran head-first into the new wave.

But the often-reluctant introduction of disco to other styles is curious and complicated. Disco is a combination of genres in itself, and the results can be extraordinary – queue Brian Eno’s “I have heard the sound of the future” pronouncement upon encountering “I Feel Love.” But love it or hate it, we must accept that we are living in disco’s shadow, with every genre touched not just by its beat and groove, but also by disco’s radical production techniques and rearrangement of format (singles, remixes, extended versions, etc.).

There was a period of collision when disco was forced upon, rather than accepted, by mainstream artists of the non-disco persuasion. Alexis Petridis writes about this phenomenon for The Guardian:

Critical opprobrium, a collapse both of sales and artistic credibility, fans who paid good money to see you baying for your blood: you couldn’t wish for a more vivid illustration of the risks awaiting the late-70s rock artist who chose to go disco at disco’s height. It was a hell of a gamble. There was always the chance of some short-term commercial gain, but the odds were stacked against you: the back catalogues of umpteen 70s artists are flecked with ignored attempts to cash in on the success of Saturday Night Fever, remembered largely by fans as catastrophic career aberrations. Even if you did get a hit out of it, your success would almost invariably be accompanied by mockery or even anger.

It’s easy to identify the artists that embraced the opportunity for experimentation versus those unwittingly dragged by their feet into the studio session. There are plenty of aberrations, but then there’s also “Heart Of Glass,” “Another One Bites The Dust,” and “Miss You.” Talking Heads would’ve been a different band without the combination of disco and their artsy ethos, and I’d argue new wave and post-punk may not have taken off without the ’70s nightclub’s groovy influence. We wouldn’t have this surprising moment from Crass either:

It’s a bit old-fashioned to mock disco — I think the consensus, finally, is that it was a significant cultural movement, not just musically but socially as well. A lot of the resistance to disco had a sinister backbone that had nothing to do with the music, as evidenced by the infamous Disco Demolition’s quick transformation into a riotous hatefest.

I remember a moment watching Late Night With David Letterman as a kid in the early-80s. Paul Shaffer would regularly have a guest fill in with the band who would often be a studio musician of some renown, though unknown to the general public. There was a drummer with the group that night and, I can’t recall who it was (though I can guess), but Shaffer introduced him as “the man who ruined music.” When Letterman asked what that meant, Shaffer explained that this drummer “invented the disco beat.” The drummer then demonstrated by playing a simple four-on-the-floor rhythm with a slight shuffle as Letterman and the audience jeered. I remember being confused by this — ruined music? I know they were joking, or maybe half-joking, but in retrospect, it seems that Shaffer — the guy who co-wrote “It’s Raining Men” — really should’ve known better.

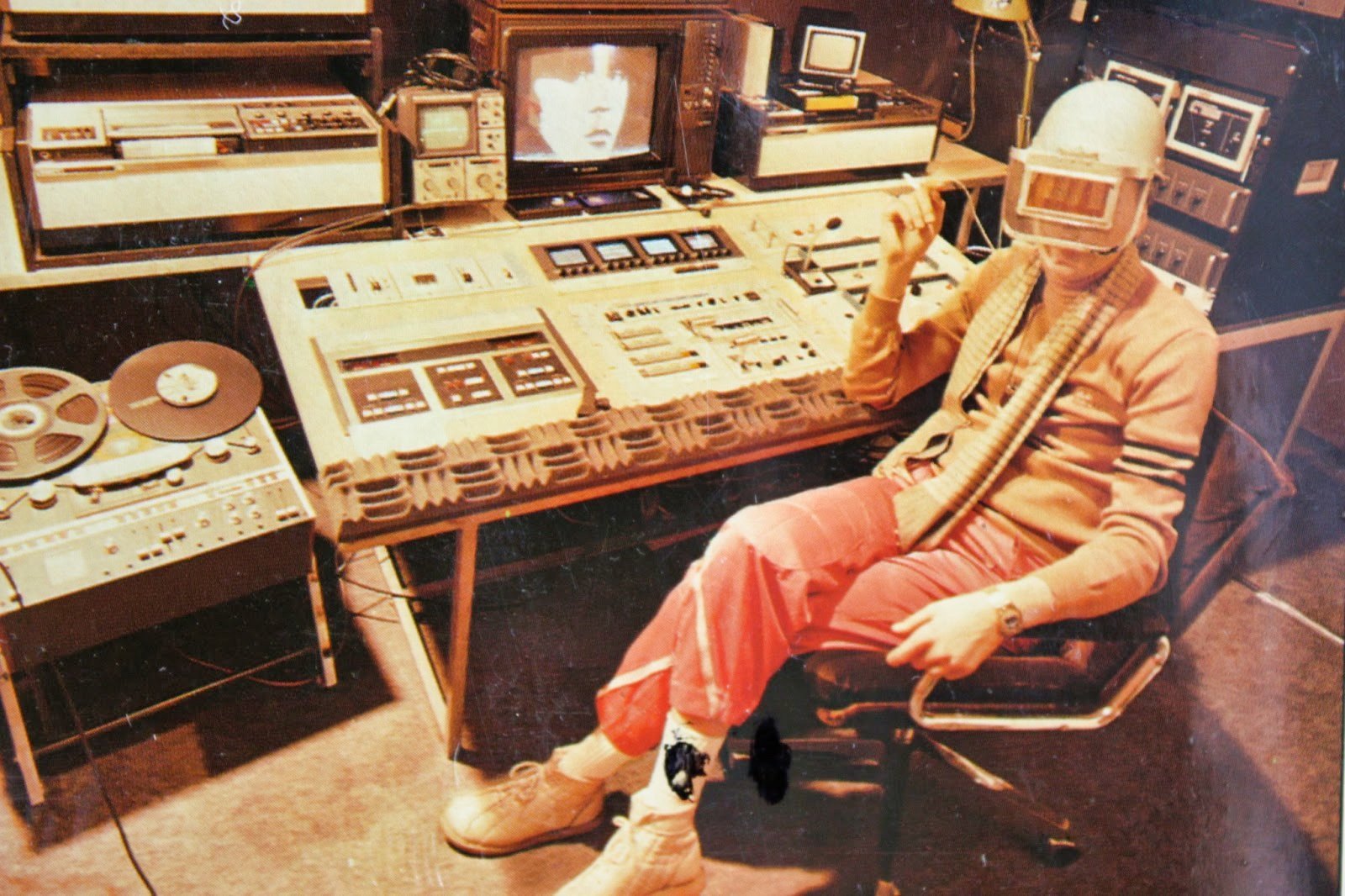

P.S. – I do realize the photo of Klaus Schulze at the top doesn’t have a lot to do with disco, but, man, it’s such a great image.