An anonymous artist paradoxically often attracts more attention because of anonymity. Curiosity draws us in for a closer look. Just look at Bansky, with mentions of his accomplishments usually sitting alongside guesses to his identity. And we can’t forget all the electronic artists accused of secretly recording as Burial throughout the end of the ’00s. The scrutiny created problems for the reclusive recording artist and, unlike Banksy (so far), he gave in to the pressure. Hua Hsu in the New Yorker:

When Burial was nominated for the Mercury Prize, a British tabloid writer tried to figure out his true identity, but was thwarted in part by Burial’s fans, who wanted him to live according to his own choices. As the curiosity about his identity started to overshadow his work, though, Burial revealed his name: William Emmanuel Bevan. Still, he refused to do interviews or to perform live shows, and he claimed to have little interest in the Internet.

Disguises became a thing, too. Artists as mainstream as Sia obscured their mugs, but there wasn’t anonymity. We know Daft Punk aren’t robots and recognize their real names (some of us even DJ’ed with them before they donned masks). There’s a purported idea of ‘let the music speak, not the image of the musician.’ But isn’t the mask, the anonymity, an image in itself? Of course, it is. And, same as the outrageous exploits of a controversial rock star (including those also disguised), it can even overshadow the music.

The Residents followed a doctrine of ‘The Theory of Obscurity.’ Formulated by the equally mysterious artist N. Senada, The Theory of Obscurity poses that an artist can only deliver their most authentic work without pressure or influence from an audience or the outside world. The Residents decided anonymity would help them follow the theory but the outside world proved inescapable. The band changed their appearance frequently through the ’70s but got stuck in the eyeball and top hat disguise for years. The image was just too popular with fans to shake.

Before Hardy Fox died in late 2018, he revealed that he was a founding member of The Residents and responsible for most of their musical output. In turn, we surmised that the still-active Homer Flynn is the ‘singing Resident,’ supplying most of the distinctive vocals. Die-hard Residents fans suspected this as Flynn and Fox acted as ever-present representatives and spokespersons for the band and their company, The Cryptic Corporation. When Homer Flynn speaks, it’s with an all-too-familiar southern drawl that those familiar with The Residents’ songs instantly recognize. Here’s a video documentary from 1991 with Flynn and Fox making appearances, and a young Penn Jillette also acting as an early-80s band representative:

(There’s a more recent, feature-length documentary titled Theory of Obscurity. It’s available to stream on Kanopy and some other spots.)

Fans whispered that Flynn and Fox were secretly the main two eyeballs in The Residents. As with Burial, the fans also — for the most part — protected these identities. And the two repeatedly denied any connection beyond their duties as managers/spokespersons. But then Hardy Fox nonchalantly revealed his actual role in a newsletter to fans a year before his death from brain cancer.

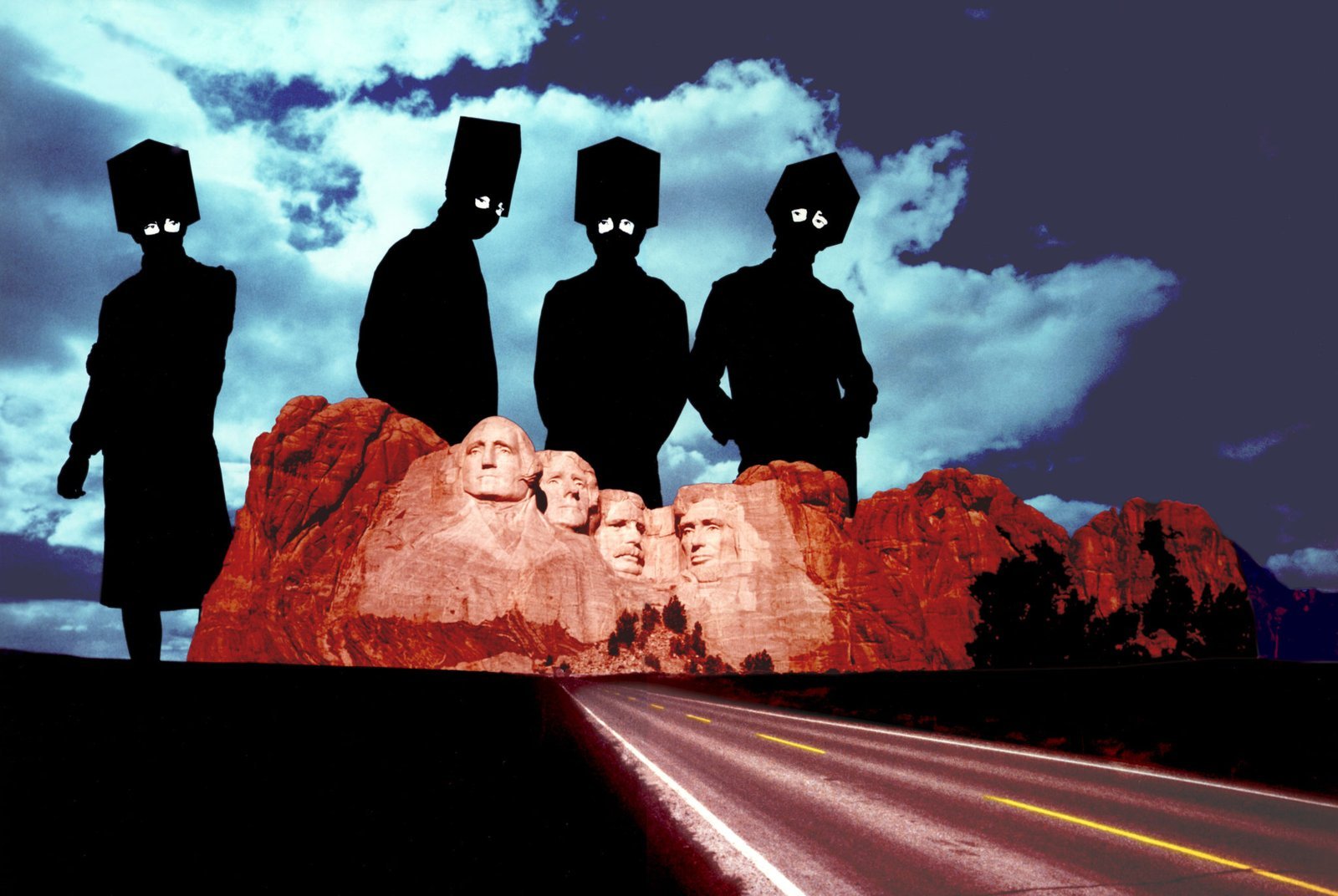

As a longtime Residents fan with a shared North Louisiana connection — more on that in a sec — I’m torn by the unmasking. The mystery of The Residents was a big part of my appreciation of the music. Again, there’s the paradox. If a purpose of anonymity is to present music without the baggage of personality, then how can the opposite result happen? It was impossible to listen to The Residents without separating them from the unearthly presences in their videos. They didn’t seem human, like they arrived in 1972 fully formed and naïve to the expectations of us earthlings and our musical norms. The mystery made them ominous, too. Just look at them here in what might be my favorite promotional photo of any band ever:

But now I think about Hardy Fox when I listen to The Residents. I think about how he met Homer Flynn in Ruston, Louisiana. They were randomly assigned dormmates at Louisiana Tech University. I went to that school for a semester and DJ’ed on the radio station for longer than that. Often I played The Residents across Ruston’s airwaves, no idea that I was paying homage to local heroes. I also think about Hardy Fox’s ARP Odyssey synthesizer, which is the star of this touching article in Tape Op. These weirdos were big-hearted humans in the end. How could they not be? But, in this discovery, the Residents lost the sinister enigma of the strange photo above.

But I also appreciate these revelations. It’s all part of the tricky business of anonymity and mystery. There’s a great quote from psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott: “It is a joy to be hidden, but a disaster not to be found.” In a way, the unveiling is a gift — we listen to the music differently with this knowledge. The songs almost become new. Even Burial’s atmospheric tunes take on new meanings to explore with a name attached, even if still not much is known about the producer.

I’ve heard The Residents’ music many times before, but now there’s a history attached. The context shifts and, in a way, the music becomes something else. “Santa Dog” is an especially wild proposition when it’s traced to these artsy outcasts, freshly escaped from a life in the Bible-belted deep south. And, now listening to the music, boy, can I relate.

This post was adapted from Ringo Dreams of Lawn Care, a weekly newsletter loosely about music-making, music-listening, and how technology changes the culture around those things. Click here to check out the latest issue and subscribe.