After playing on famous albums by George Harrison and John Lennon, drummer Alan White joined Yes just before their next tour, on three days’ notice. That’s notable because those Yes songs (and Yessongs, a live set culled from that tour, is the first album Alan played on) are complex, baroque beasts filled with time-switches and dastardly riffage from which no instrumentalist can escape. He passed the audition and was Yes’s key skin-pounder for the rest of his life. And that life, unfortunately, ended for Alan White this week.

I’ll argue that Alan White is one of the most influential drummers of our time, though I bestow the title fully knowing that his influence is involuntary. You see, Trevor Horn bought a Fairlight CMI sampling keyboard with his formidable “Video Killed The Radio Star” royalties, setting him back a cool £18,000. “You could buy a house,” he says about that purchase. But Trevor sniffed the future. He parlayed this new device to help get his early music producer jobs — bands not only enjoyed Trevor’s production chops but also exclusive access to this wizardry machine. Malcolm McLaren and ABC came calling.

Trevor assembled a team to help out on those two productions, with Gary Langan on engineering duties and JJ Jeczalik managing the ins and outs of the frustratingly complicated Fairlight. The great Anne Dudley also appeared, contributing string arrangements and keyboard expertise. This crew then worked on Yes’s 90125 album, home of the breakout song “Owner of a Lonely Heart.” Yes’s dated prog-rock pomposity unexpectedly gave way to Trevor’s unmistakable sonic touch.1Yes’s previous album Drama is also worth a listen as it’s where Trevor Horn first collaborated with the band — as their lead vocalist!

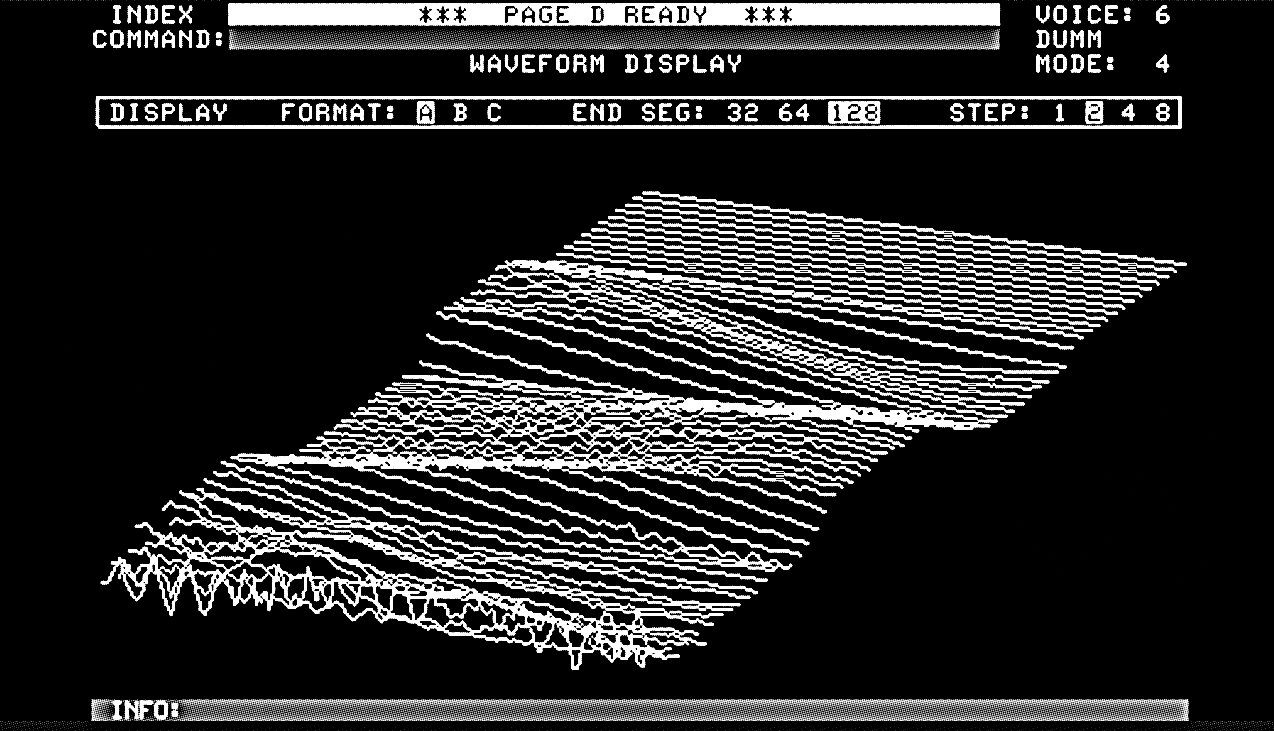

As legend has it, JJ Jeczalik and Gary Langan were lingering in the studio after a Yes session, fooling around with the Fairlight. They thought it would be novel to take a discarded drum track from Alan White and feed it into the Fairlight’s Page R sequencer. Wikipedia claims (and I have no reason to doubt) that this was the first time an entire drum pattern was digitally sampled.

Fast forward a few months, and this production team formed The Art of Noise around these Fairlight experiments with the assistance of writer and media wrangler Paul Morley. And, as a result, that’s Alan White you hear sampled, cut-up, and processed-to-hell on the seminal songs “Close To The Edit” and “Beatbox.”

Not only is it likely that Alan White was the first drummer to get captured in a sampler’s Phantom Zone, but those beats went on to inspire whole genres of hip hop, breakbeat, big beat, and so much more. I doubt there’d be a Bomb Squad without Alan White and that night of Fairlight tomfoolery, and, really, that’s all you need to know. Today’s music wouldn’t be the same.

Curious about this vintage alien technology called a Fairlight CMI? Someone made a video with the sampler and replicated the creation of “Beatbox.” The display graphics seem right out of a dashboard screen on the USCSS Nostromo:

Side tale: When I heard (Who’s Afraid of) The Art of Noise? I was instantly obsessed. I couldn’t figure out how this music existed, and I needed to know. In my knowledge quest, I learned about this amazing new thing called a digital sampler. I had to have one, but I didn’t have £18,000 lying around. So I made a list of all the things I’d eventually sample once I got ahold of one: household appliances, my friends vocalizing, various neighborhood pets, and so on. When I finally got my first sampler, a Casio SK-1, I was frustrated by its limitations and couldn’t act on over 90% of my list. But it was still a formative blast. That weird little keyboard and a few tunes sampling the drummer Alan White were responsible for pushing me down the music production path.