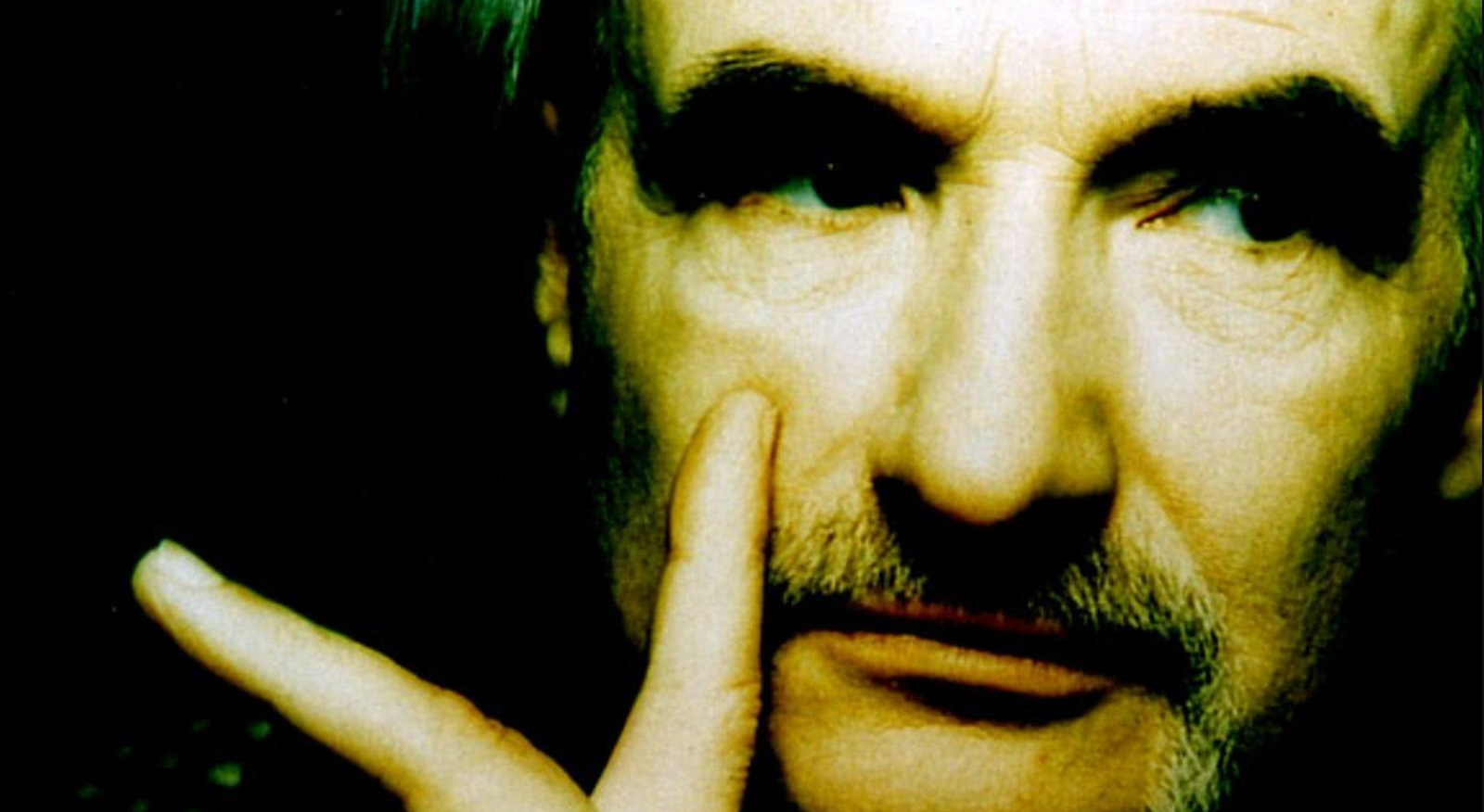

I’ve been slowly gathering some thoughts about Mark Hollis. His passing hit hard for many in my circle. Maybe it’s because it seems like we abandoned him, like an old friend we haven’t kept in touch with and then we hear he’s departed. The distant and enigmatic Hollis was like an old friend if only in that his music was so personal, the most personal music. And that we’ve been secretly rooting for him — Mark vs. the record companies, Mark vs. the accepted rules of music, Mark vs. notoriety, Mark vs. everything we’ve come to expect really.

Mark Hollis was the frontman for Talk Talk; a band initially positioned as a groovy new wave thing, akin to that other repetitiously named act, Duran Duran. But even in the early days, Hollis spoke about weightier things when interviewed — philosophy, Krautrock, Erik Satie, and other like-minded interests — betraying a more profound ambition. With each album release, the music got artsier but not without some hits, allowing the band to request and receive creative control for the 4th long-player, Spirit of Eden.

You may know how this plays out. A sparse, emotionally raw, and obtuse record, Spirit of Eden mystified its label (EMI) to the point of a lawsuit. As happened to Neil Young a few years earlier, the label sued Talk Talk for being intentionally uncommercial. Hollis and the band soldiered on, parting ways with EMI and recording the equally beguiling Laughing Stock for the newly relaunched Verve Records. The group broke up, Hollis went silent — for the first time — and reappeared for an even sparser, even rawer, even

Then Hollis quietly disappeared. He hinted that he preferred to be a dad than a musician in the public eye. And soon these albums — including EMI’s problem child — were hailed as masterpieces, intensely beloved by their listeners.

I think the first Talk Talk album I ever heard was Spirit of Eden. Of course, as a teenager, I loved “It’s My Life” — and its brilliant Tim Pope-directed video, which EMI also reportedly hated — and “Life Is What You Make It,” but Spirit of Eden was my first Talk Talk full-length experience. It haunts immediately at first listen and, at the time of its release, like nothing heard before. I’m somewhat disappointed that I didn’t listen to Talk Talk starting with their very first albums, to get to know them as one thing and then experience them stubbornly transforming into another.

I want to believe Mark Hollis didn’t disappear because he was frustrated or let down by a lack of success. All evidence points to success not mattering to him. I feel he put everything out there and there was nothing left. Not in a sad, spent way. But that he made his statements, provided the inspiration for others to carry, and silently stepped aside. Finished and satisfied rather than sad and frustrated.

It’s curious that fellow Mark Hollis fans seemed to pick up on this. No one I’ve spoken to feels deprived of new music, that he owed us a surprise album over these past two decades (compare that to our demands on the similarly hidden My Bloody Valentine). But it makes sense, especially now that I re-listen to Hollis’s solo album. How could music this intimate be accepted now that everyone’s yelling and busy, in a constant state of rebuke? Mark Hollis’s music is endemic of a different century.

I have enjoyed — in a reminiscent, melancholy way — all the beautiful tributes and classic articles I’ve been reading about Hollis. I’ll close with a selection of excerpts from some of those.

Andrew Kirell in The Daily Beast

The crass commercialism of the music industry has long beaten down artists by placing emphasis on the superficial—in the ’80s, this meant heavily curated fashion-centric personae; and today, it’s an unbearable pressure to polish your social-media persona before your own artistry. … Hollis rejected any such norms, uncompromisingly pursued his own vision, and thus inspired countless fledgling artists to stay true to their craft in the face of commercial pressures. {…}

His music served as the holy grail for music lovers—people who love music not just for the stimuli but for the craft itself and how it serves as a portal into the artist’s mind and into worlds they cannot explore on their own—as Hollis, himself a music obsessive, rewarded listeners who are in constant pursuit of answers on how music works.

Alan McGee (Creation Records) in The Guardian, from 2008:

Spirit of Eden has not dated; it’s remarkable how contemporary it sounds, anticipating post-rock … it’s the sound of an artist being given the keys to the kingdom and returning with art. {…}

I find the whole story of one man against the system in a bid to maintain creative control incredibly heartening.

Jess Harvell in Pitchfork, from 2011:

Unlike many reclusive musicians, though, you won’t feel that Hollis absented himself before his overall project was completed. These albums still stand a good chance of alienating you, but if you find yourself vibrating sympathetically to them, there’s enough mystery and beauty in them to sustain a lifetime’s listening, whether Hollis or Talk Talk ever record another note.

The fanatical care that went into the recording of Spirit of Eden and Laughing Stock — the limpid production, the teeming of tiny details, the leaps from hushed softness to squalling harshness — have turned these albums into fetishes for a generation of soundheads. But although their audiophile allure is a factor, these albums conquered hearts through their emotional power — the naked ache of Hollis’s vocals, the oblique bleakness of his lyrics. On Spirit of Eden and Laughing Stock, two kinds of beautiful emptiness confront each other — the stark grandeur of the soundscape, the desolate neediness of the man alone within it.