I knew David and Jennifer long before they became Mr. and Mrs. Kraftwerk. Actually, David and I used to pal around in college, performing on-air hijinks on college radio stations and attending Butthole Surfers concerts. There was always a performance art aspect to David’s humor, probably spurred on by the mischievous subcultures you’d find sneaking around late ’80s campuses. As the Subgenius slogan went, “Fuck ’em if they can’t take a joke.“

The honorary title of Mr. and Mrs. Kraftwerk was unwittingly foisted upon David and Jennifer. As you’ll learn, David is the fabled Florida man who changed his name to ‘Kraftwerk.’ Or so they say.

As self-described ‘super fans’ of the German uber-group, David and Jennifer at first happily embraced getting tangled in the mythos of Kraftwerk. Now they unashamedly encourage and propagate it. If this were one of those movie ‘expanded universes,’ you’d have to now refer to their contributions to the Kraftwerk story as canon.

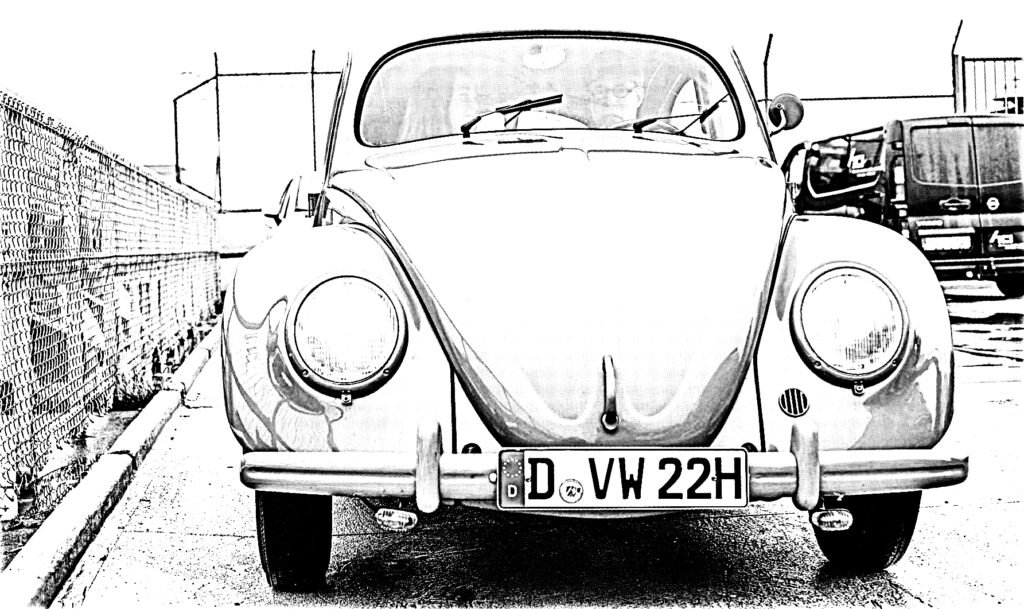

This post breaks down the timeline of David and Jennifer’s Kraftwerk-related activities, projects, and art pranks. A common theme is the automobile — what begins with a memorable driver’s license photo ends up with the five-figure purchase of the very Beetle spotted in 3D at Kraftwerk’s current shows.

You won’t be surprised to learn this list is incomplete. There are the gingerbread cookies, the BBC Radio interview, the Computer World computer project, the new concert-going outfits, the teletubbies, and so much more. Like musique, this project is non-stop. The tale of Mr. and Mrs. Kraftwerk is an ever-developing story.

The transcript below is taken from a much longer conversation — nearly 45 minutes, in fact. The full interview goes into many other Kraftwerk-related shenanigans and some nerdy details. You can listen to it all in the handy audio player below.

❋-❋-❋-❋-❋-❋-❋-❋

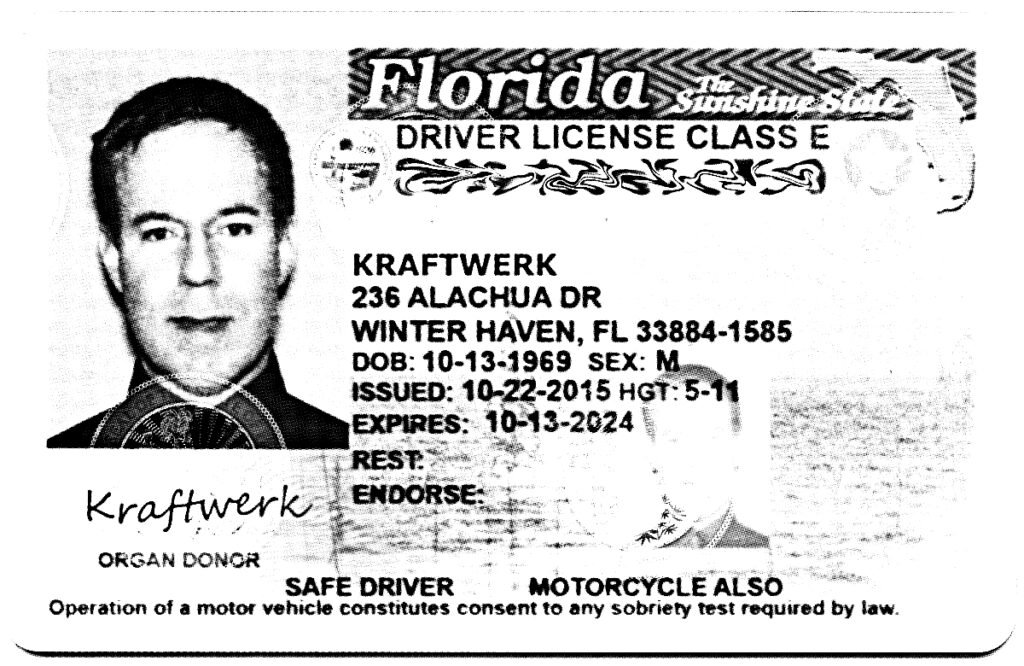

FLORIDA MAN CHANGES HIS NAME TO KRAFTWERK

David: When we moved to Florida, we had to get new driver’s license photos.

Jennifer: And David went to the DMV as Man Machine. And specifically asked the photographer to make sure that his — I don’t know how you managed to pull this off — but get your shirt and tie in the photo because they always cut it off at the Adam’s apple. The fact that you were able to ask for that, without it raising any red flags or strangeness, and them doing it — kudos.

Michael: Was that the same day that you took all the other photos of Man Machine out and about?

Jennifer: Yes. Because since he was already in costume, why not continue taking photos, documenting this costume, and then doing things that are out of character for a Kraftwerk robot.

David: You mean like having humanity?

Jennifer: Yes. Like doing something other than standing motionless on a stage.

David: So we fed some ducks, put some gas in the Subaru, and enjoyed some delicious iced coffee. Then at the end of the day, I went to bed.

Michael: Then you posted the photos online.

Jennifer: Yes. It took about six or eight months, and then somebody found them and just made up a story. They didn’t reach out or contact anybody.

David: It was Dangerous Minds. And they made this whole story up based upon the photos. Florida Man Changes His Name to ‘Kraftwerk.’ I woke up that morning, had a cup of coffee, and took a quick look at my social media feed. At that point, I’d already had like 50 notifications, and I was puzzled.

Michael: And then it ballooned from there!

David: Nevermind that Vice Magazine interviewed me, and Road and Track got in contact because of the DMV end of it. Oh, and New Music Express wrote a story. Nevermind that. We were in Lakeland, Florida, of all places, at a record store, and somebody started whispering, “Hey, it’s that’s the guy. That’s the guy who changed his name to Kraftwerk.”

Jennifer: It was finally a bit of fun news about a Florida man. Nothing that involved an alligator or an arrest.

David: It was probably the first positive Florida man story to be written in a decade.1You can read David’s ‘inside story’ of this experience here.

THE KRAFTWERK WEDDING

David: We were planning on getting married, and I half-jokingly said to Jennifer, “What about Kraftwerk as a wedding theme?” And she wasn’t half-joking with her answer. She was full on.

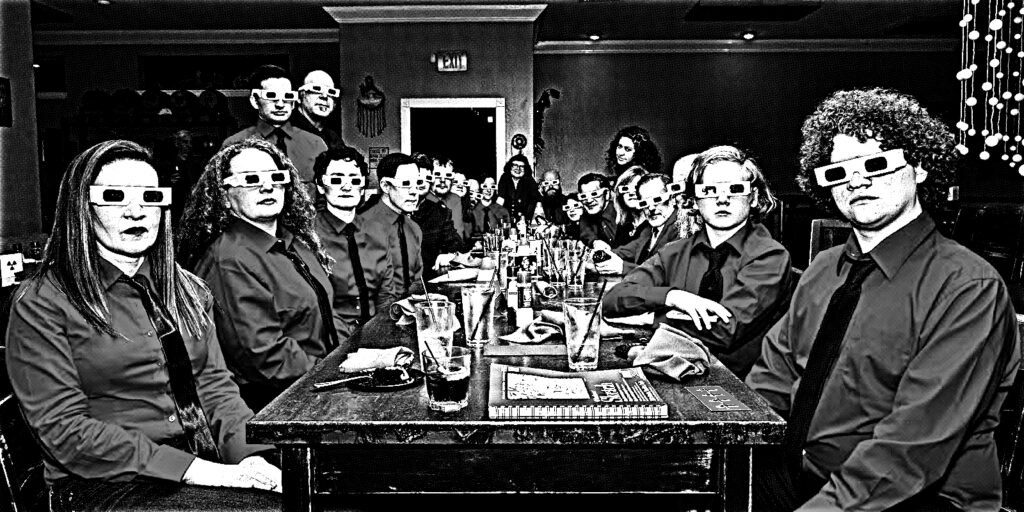

Jennifer: So a red shirt and black tie were obvious attire for all of the wedding party, including me. Then we made two Kraftwerk podiums. They’re like lecterns but are actually the cases that they stand in front of when they perform. We found some traffic cones that didn’t have stripes and proceeded to mask them off and spray paint them, give them stripes. And when we went to see Kraftwerk in Atlanta, both of us had the foresight to collect as many discarded 3D glasses on the way out of the venue as possible.2There’s a lot more that went into this wedding — read this blog post.

Michael: And everyone dressed as Man Machine.

Jennifer: Yes. That was the only request.

Michael: And the wedding got written up in a bunch of places, including in Germany.

Jennifer: Yes, in the Rheinische Post in Düsseldorf.

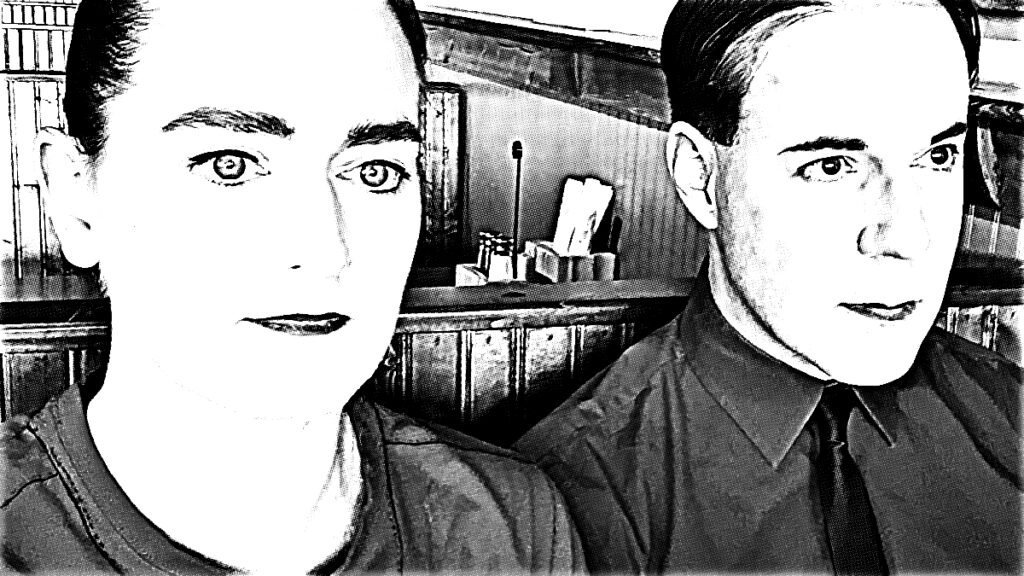

KRAFTWERK’S NEW PRESS PHOTO

Jennifer: We reached out to a photographer friend named Jon Wolding. Sort of last minute, maybe a month before the wedding, and told him our idea.

Michael: This is the photo taken at the end of the night, replicating the Man Machine album cover.

Jennifer: He managed to pull it together in the back parking lot; that’s the exit staircase of the second level of Ella’s. He stuck some red photo paper to the outside of the building with gaff tape, and he and his, team managed to set up and light that amazing photo.3Editor’s note: Yes, I am one of the four participants in this photo.

Michael: Then, unexpectedly, the photo starts appearing in strange places.

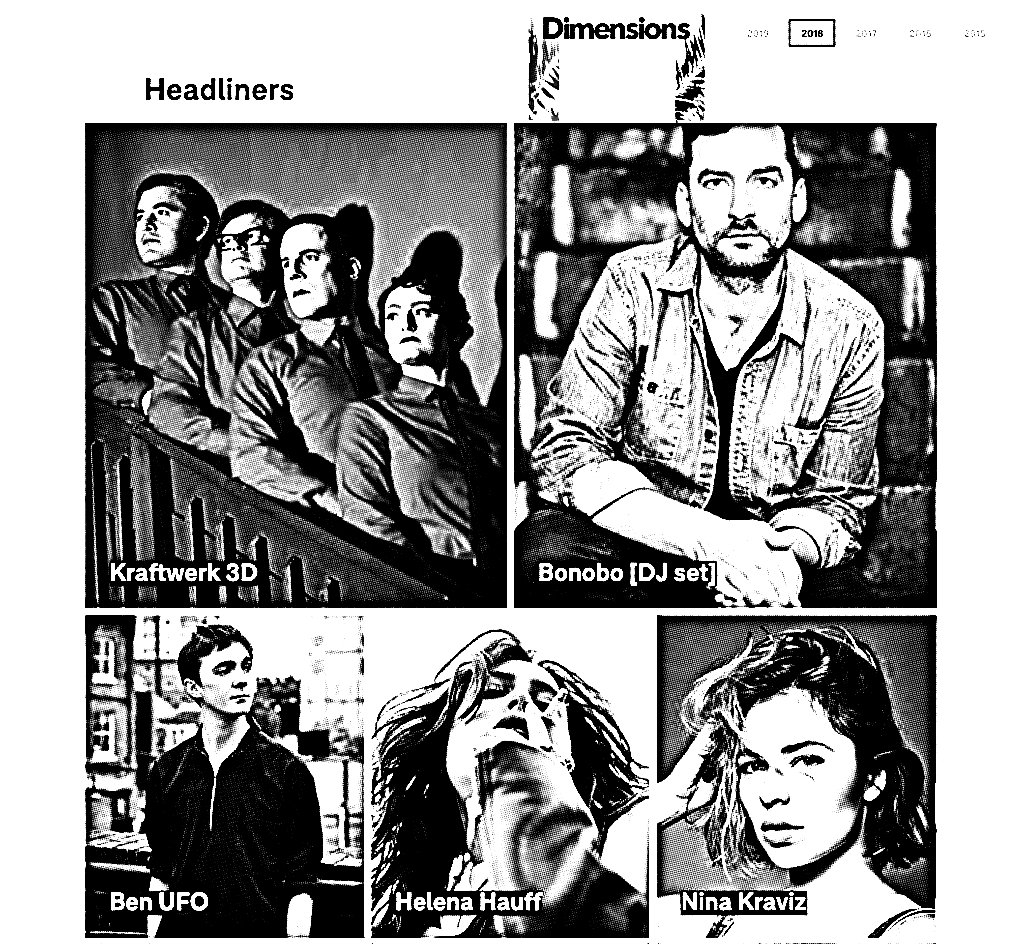

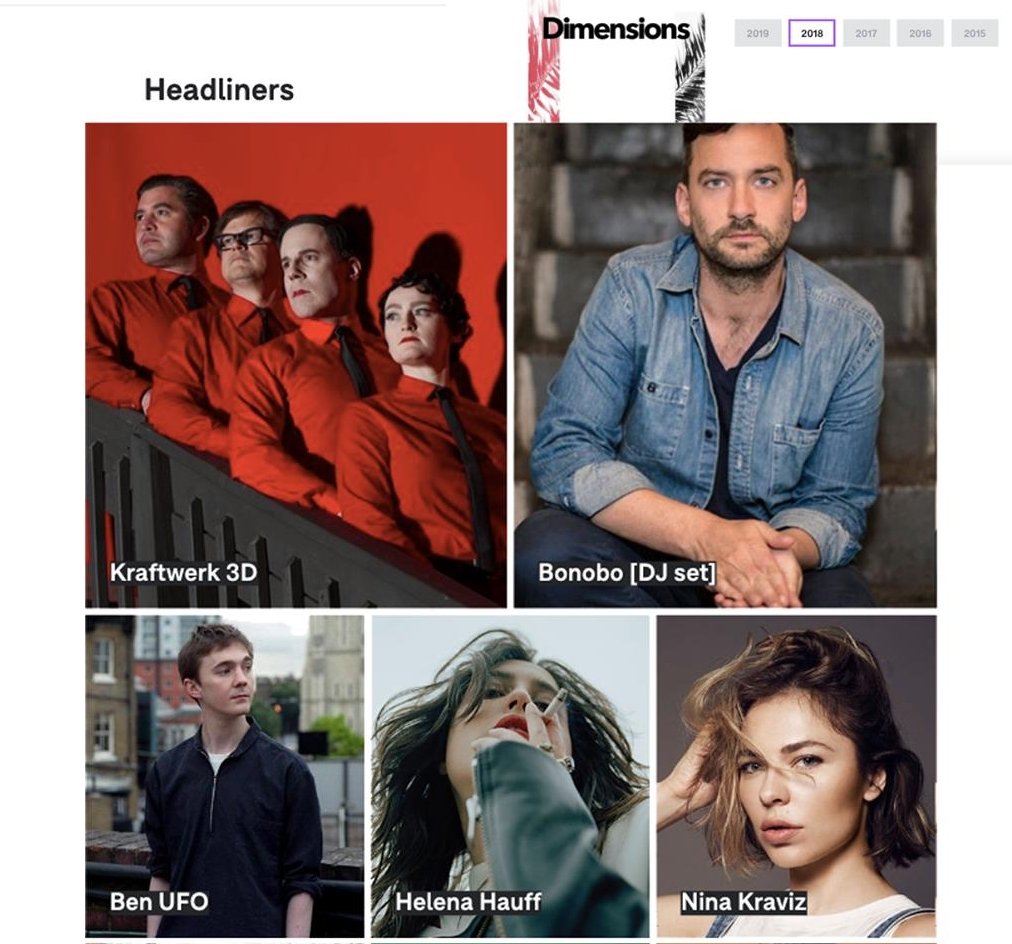

David: It was at a music festival in Croatia. The Dimensions Festival 2018. And, on their website, they used our photo as the photo of Kraftwerk, the festival’s headliner. And if they printed flyers and posters like that, I would pay a King’s ransom for one.

Michael: I think what happened is somehow, through rampant sharing, the picture built enough SEO credibility that it somehow marched its way to the top of an image search result for ‘Kraftwerk.’

David: Yeah, apparently that’s what happened. And then there were other things as a result of that. Like bandanas and other apparel being sold on Amazon with our wedding photo on them.

KRAFTWERK SKY DANCER

Michael: What was the next project?

Jennifer: We carved the pumpkins for Halloween. Then, soon after, around Christmas, the neighborhoods here are full of those inflatable Yodas and Santa Clauses and stuff. And I thought, “Wouldn’t it be fantastic to have a Kraftwerk sky dancer?” I mocked it out on packing material paper and got some ripstop nylon, and sewed it together.4Jennifer will show you exactly how she made the sky dancer in this blog post. And I found a guy on Craigslist that had a surplus of wind sock fans. I don’t know why. We did a test run out in the front yard, and it worked! But now we need to find someplace with a nice backdrop for a video. So we guerrilla-style drove up in the backside of the Tampa Museum of Art, put the hazards on, wheeled the fan and the sky dancer out, and plugged it into an outlet. That’s the video that you see of the sky dancer video on YouTube.5Be sure to read David’s blog post for more detail on building the sky dancer.

David: You should make it very clear: we tried to get them to sign off on it. They just looked at us like we were offering a lightly fried weasel in a bun. So, we had to take matters into our own hands and just go do it.

Jennifer: Since we had met Wolfgang Flür,6A meeting which you can read about in David’s excellent blog post. it seemed logical to put his face on the sky dancer. So it’s a Wolfgang Skydancer, which he thoroughly loved. And he’s used that video footage in his recent concert backdrop video.

KRAFTWERK PUPPETS

Jennifer: The puppets were also an idea that I’d had, but, again, how to get from an idea to making something three-dimensional — I didn’t know how to do it. And it occurred to me that maybe I should look on YouTube. And sure enough, Adam Kreutinger has a whole how-to one-on-one series on making puppets.

David: And Jennifer vanished down a puppet rabbit hole, like a wormhole in space and time, not to be seen for months.

Jennifer: So now we’re the proud custodians of four rather large Muppet-sized Kraftwerk puppets,7Jennifer documented the creation of the Kraftwerk puppets in this Flickr album. which we used to shoot a video set to the “Autobahn” cover by New David.

David: New David did a lovely cover of a number of Kraftwerk songs. I think that his cover of “Autobahn” is the most significant because he takes a song that is intrinsically very synth-laden and with no real-world instrumentation, and he turns it into an ode to a drive in the country. And it’s beautiful. We were listening to it and had the idea that this was something that we could do a video for. We began working on an homage to New David’s homage. Then I got in touch with him and said, “Hey, can we use your music for our video?” and he was all for it. It worked out well, and the rest is history.

FLORIAN SCHNEIDER’S BEETLE

David: And then the bad news came.

Michael: Which was Florian Schneider’s passing.

David: Yeah. It was a large loss. You could feel it. For us, it was like, and I guess, how the world felt about the loss of David Bowie except a little more poignant. I wrote a story about the 26 days of silence following Florian Schneider’s death on Medium, and I led that story off with a photo of his Volkswagen Beetle. But we didn’t know about the car going up for sale until Claudia8Claudia is Florian Schneider’s sister. You’ll have to listen to the full interview in the player at the top to learn how she figures into this tale. ‘at mentioned’ one of us on social media about it being for sale on the German equivalent of Autotrader.

Jennifer: The more we thought about the opportunity, it seemed that we should at least make, as they say, the college try. We should at least reach out to the dealer, give him a little backstory on who we are, why we’re interested in the vehicle, what we’re prepared to spend on it, and ask, was he willing at all? Is it possible for him to make any kind of compromise on the going price?

David: Obviously, you don’t have a good idea what sort of value to place on the 1949 Volkswagen Beetle owned by Florian Schneider. It’s hard to wrangle a price, especially when you’re doing it over a phone line regarding a car that you’ve never laid eyes on in person. So I laid out the case for the two odd-ball Americans, so very far away from the Beetle’s homeland in Germany. He felt certain synchronicity with us, and he was willing to do it.

Michael: So then the car had to get on a boat, but did you go there to see it first?

David: Yes. We really wanted to go see this car in its home, before it came over. And so we went, and that afforded great opportunities to meet journalists who suddenly found our purchase of the car to be very, very newsworthy.

Michael: So once again, the news cycle kicks into gear.

David: I don’t remember the journalist’s name who wrote the story in the Süddeutsche Zeitung, but that newspaper is the German equivalent of the New York Times. It has national distribution across Germany, and Germans are fanatical readers of the newspaper. It was a really big deal. And the story was on page three of their A section. It didn’t go in the C section or the D section. It was page three and the entire page, top to bottom, in the A section. Because the Germans took a great interest in the idea that this piece of their cultural heritage was going to get loaded on a boat and go to Florida for two American Kraftwerk fanatics.

Jennifer: And then the car got on a boat for what we thought was going to take a month. It turned out to be closer to four and a half.

Michael: Well, the car finally arrives, and you’re ready for it. And you’re able to fully document the arrival.

David: (Laughter) There was a lot of emotion; it’s going to be here any day. Now we were thinking, with great confidence, they will definitely give us notice before it gets here. Except that there was zero notice. I happened to be up, and I heard a noise outside at 1:30 in the morning. I peek out of the blinds, and there’s this enormous automotive transportation trailer. They’re offloading cars, and I think, “Oh, that can’t possibly be for us. They must have had a flat or something.” I walk out there in my jimjams and my bed head with a flashlight, and sure enough, at the back of the trailer is our Beetle. And we were prepared to have a friend of ours do videography and document the joyful reunion of us with Florian Schneider’s Beetle. And instead, it’s me holding my telephone at arm’s length with bedhead and trying to pretend that I’m happy.

Michael: Would they have left it in the street if you hadn’t been there?

David: I can’t tell you. I regret walking outside as I’d like to know what they would have done.

Michael: So, then, what are the plans for the Beetle?

David: The plan is to bring it to Volkswagen events and show it not only as a fantastic, very close to the war post-war artifact but also as a piece of German cultural heritage. Perhaps with a cutout of Florian Schneider and some Kraftwerk playing.9and hopefully Wolfgang Skydancer dancing alongside!

Michael: Do you foresee driving around in it?

David: Well, we still need to finish its legalization in the state of Florida. But you know, a lot of terrible yet ironic things seem to happen in this world. And it would be just totally ironic and terrible if a distracted person sending a text were to t-bone this car while in Tampa traffic.

Michael: And driving a neon pink modern Volkswagen.

David: Yeah. So, while it will occasionally be driven, it’s only going to be under the auspices of a Sunday morning drive while all the particularly bad people are still in bed, recovering from hangovers. It will get taken to car shows, but we’re going to get a nice flatbed trailer to transport it. To that end, we purchased a tow vehicle: a big white GMC truck. And Jennifer is in the midst of making some amazing vinyl graphics that are going to be on the side.

Jennifer: I’ve already purchased little metal letters for the back tailgate. This truck is now the Kraftwerk Edition GMC truck.

David: It looks very official.

KRAFTWERK IS THE REASON

Michael: I’m curious — besides being big fans, what do you feel makes Kraftwerk ripe for this?

David: It’s the absurdity of having a sense of humor about a band that takes itself so seriously. Or, more accurately, whose fans take the band so seriously. I don’t know that Kraftwerk take themselves that seriously …

Jennifer: Their fans sure do.

David: But the fans do. Talk about a bunch of killjoys.

Jennifer: Kraftwerk has created such a simple and bold pallet to pull from: vivid colors, vivid shapes, iconography, symbols … like visual samples that can be reused and reconstituted and put together in completely new and different ways. And I like putting things together in ways that are incongruent with this severe hard visual aesthetic that’s been put out by the band.

Michael: I also think the mysteriousness of them allows people to fill in their own blanks. And, to me, you’re starting to take on sort of a Kraftwerk-ian version of The Yes Men.

David: Thank you for drawing that analogy. That’s good.

Michael: It’s this idea of these intentionally bizarre things putting a stop to people’s normal brain processes and making them think in ways they’ve never thought before in order to try to figure things out.

David: That was the tenant of the surrealists. And that’s kind of what we hope to achieve. There’s an absurdity that we want to poke at to the point that it makes people uncomfortable. I mean, we are super fans, but at the same time, we’re also kind of trolling the super fans.