I have some curatorial notes today. Memora8ilia, the “filing cabinet for 8sided.blog,” is presently hosted on Tumblr. I’m in the process of moving it to a self-hosted site, at which point I’ll get more active with it. I’m not necessarily moving it off Tumblr due to recent controversies. However, that does serve as a reminder that when we rely on other platforms to present our creative work, problematic associations can (and probably will) happen.

Memora8ilia is meant to be a place where I store cool things I find on the web in case I want to find them again. It’s inspired, in part, by Warren Ellis’s LTD blog, which is his “writer’s notebook” and daily log that we, his readers, are allowed to access. Warren logs what he’s reading, watching, and hearing, as well as updates on how his garden is faring (a source of both his joy and frustration). He often checks in with his morning status and what his workload looks like for the day. Warren claims the people he works with can use that status to gauge how slammed and accessible he is at any time. I won’t go as far as posting my status, though. For one thing, the people who I work with should always consider me slammed and pretty much inaccessible lol.

Memora8ilia’s just fun stuff, and you’re welcome to follow along. Sometimes, things I briefly add to the Memora8ilia filing cabinet stick in my brain, and they work their way over to this site. That process is interesting, and I like having a record of it happening. So, look for that to pop over to its new home soon. I don’t think I can transfer the Tumblr site posts over to the new one (which will be a WordPress thing). It’ll be a fresh start. I’ll keep the Tumblr archive up and create a post at the top with a redirect once the change occurs.

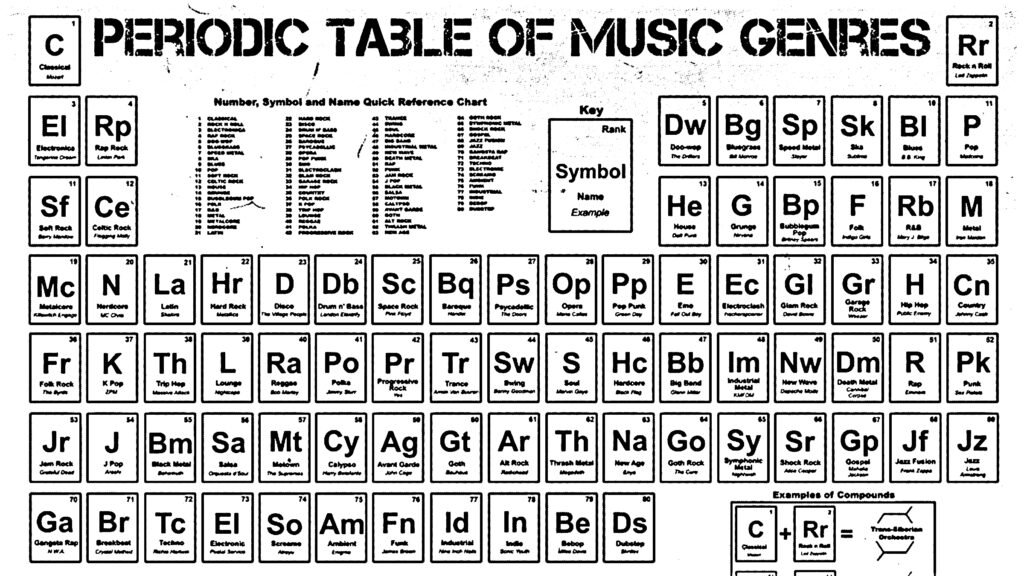

More curation? This Beginner’s Guide to Chinese Shoegaze, courtesy of Concrete Avalanche, is so uplifting it makes my entire body tingle. And Simon Reynolds dropped a blog post about the “two kinds of early electronic composition and musique concrete that I really really love, and can’t get enough of” and helpfully supplied embedded YouTube examples. Your Discogs want list just got a lot bigger. On the niche (my kind of niche!) side of things, check out Harvard’s Davis Center Library Poster Collection, solely featuring digitized “Soviet posters dating from 1919 to the 1990s.” Be still my heart.

There’s also the music I am posting in these blog entries, whose curation, from the outside, appears a bit higgledy-piggledy. Well, posting only the latest music isn’t something I’m that concerned about. That’s a good thing because, as this blog goes through its long pauses, the music piles up. This particular pile consists of music I’ve purchased on Bandcamp with the intention of mentioning on the blog and releases sent to my inbox by kind and understanding labels and artists. I’ve thrown all this music in a folder, and when it’s time to concoct a post here, I use my handy-dandy randomizer and see what it pulls out. Surprise!

Today, I rolled a 244, and that points me to Andrew Edward Brown’s “Her Rescue.” Andrew is a Los Angeles-based via Philadelphia producer who also records under the alias Champion Soul and in the collaborative project Andy & Sasa. “Her Rescue” is one of the tracks found on Mr.Brown’s Studio Sessions Volume 3, an EP released by Strange But Soulful (could be a little stranger, tbh). The other cuts on the EP aren’t my thing, but “Her Rescue” has a hazy simplicity that harks to that time when techno producers were loudly proclaiming jazz bona fides. “Her Rescue” has all those elements: a gently percolating synth sequence, four-fingered chords on analog gear, and spacey treble strings, all riding on a kick drum shaker cycle. There’s saxophone, too, but I don’t mind as it’s reverbed and restrained and works a lot better than the Blade Runner love theme. This stuff is real fuckin’ sexy, just like you asked.

I also want to take some time to pour one out for Creature, AKA Creature Feature Double Feature, pictured at the top in a senselessly abstracted portrait. This exceptional cat, who enjoyed giving me determined head butts at three in the morning as I was fast asleep, was a part of our household for 17 years. Impressive! And a couple of days ago, he decided to wander off into the good night, likely not to be seen again. That fellow never had an awful day in his life — especially that day when he caught a squirrel (bad Creature!) — so our sadness is tempered by the appreciation that anyone could be so lucky to have 17 wonderful consecutive years. Off you go, sir, and farewell.