David Lynch Gives a Lesson in Sound Design

David Lynch is relieving his lockdown boredom by posting videos. He gives weather reports (nothing new for him), baffles fans with what he’s working on, and declares a daily magic number. If only I could get a couple of hundred YouTube views from pulling numbers out of a jar.

In addition to documenting these quaint activities, Lynch’s team is also posting a series of short films under the David Lynch Theater series. I don’t think many, if any, of these are new, but most are new to me.

So far, my favorite is the deceptively simple one-shot video, The Spider and the Bee. The mini-movie consists of a close-up shot of an unfortunate bee caught in a web as a spider enacts its fate. There’s no semblance of Hollywood production here, and it’s a solid guess we’re looking at an undusted window sill in Lynch’s house. It’s Lynch, not Attenborough, after all.

The scene lasts for eight minutes, a challenging length for a real-time display of a struggling insect. But I found the video transfixing, my attention aided by the remarkable sound design. Evocative use of sound is a Lynch trademark, dating back to the hisses, hums, and whirrs found in the Eraserhead score. Sound is dramatically and innovatively used to accent images and nestle implications through Lynch’s entire oeuvre, right to the recent Twin Peaks series. If you pay attention to final credits, you’ll notice Lynch is always partly or solely responsible for the sound design on his projects. And The Spider and the Bee is an experiment in sound design.

With only natural sound (or no sound at all), the video’s nothing special, a ‘circle of life’ home movie shot on a lazy day. Add the sound — the bee’s hapless buzzing, the spider’s cartoonish clicking, the swoops as the spider slides — and the story becomes compelling. The viewer is brought into this, too, as the camera thunders as it quickly changes angles. I jumped out of my seat the first time that happened.

Sound is an effective contextualizer, and inventive sound design, even when subtle, can transform a visual storyline into something heightened and unreal. It’s a fun trick played on our brains.

Bonus points: check out the documentary Making Waves: The Art of Cinematic Sound.

Incendiary and Extraordinary

• Tomorrow is Juneteenth, and it’s the first Juneteenth that Bandcamp is donating all of its 15% sales take to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. They’ll also allocate “an additional $30,000 per year to partner with organizations that fight for racial justice and create opportunities for people of color.” I say it’s the first as Bandcamp pledges to make this an annual thing. Many artists and labels are following suit, promising their sales shares to civil rights organizations, too. So, hey — let’s grab some music. This event is an excellent opportunity to revisit this Reddit discussion on Black ambient and experimental artists to support and this searchable site of Bandcamp’s Black-owned labels and artists.

• Here are a couple of quick links to incendiary and extraordinary examples of Black art: the 1986 film Handsworth Songs is experimental documentary filmmaking at its best, via John Akomfrah and the Black Audio Film Collective; and this NY Times article from Marcus J. Moore compiling ’15 Essential Black Liberation Jazz Tracks.’ [LINK] + [LINK]

• Twenty Thousand Hertz is an informative podcast that delves into the “world’s most recognizable and interesting sounds.” The latest episode is about a topic near-and-dear to my heart: music copyright lawsuits. The host, Dallas Taylor, examines the ‘theft or inspiration?’ dilemma and lucidly explains the legalities. The podcast episode serves as a good explainer for those who want to know more about the topic and has a few interesting new perspectives for been-down-that-road folks like me. For what it’s worth, I don’t think any of the cases brought up in the episode should have gone to court. I do understand the potential dangers of broadly loosening our parameters on copyright, but letting experts decide on music theft disputes rather than a jury is a better idea. I wrote more about this topic here. [LINK]

• As you know from previous ramblings, I’m thinking a lot these days about how I use the online medium and the digital footprint I’m leaving. I’m playing around more with micro.blog and this site’s connected ‘micro-8sided’ blog. I’m trying out an idea of the microsite as an idea repository — a placeholder for things I’m reading, listening to, and thinking. It looks like this: short ideas and notes jotted down in the microblog, longer and better thought-out pieces on this ‘main’ blog and the email newsletter. I can use the micro to access things that grabbed my interest, expanding on some of those topics here and in the newsletter. That means the microblog provides a peek at what I’m thinking about as a preview to topics appearing here. At least, that’s how it works in theory. I may chuck it all later this week, depending on how time-consuming a labyrinth of thought this turns out to be. Oh, and as I’m lessening my presence on targeted-ad-fueled social media, micro.blog now crossposts to Twitter, and I’ll aim to visit that place less and less. Bye-bye to Facebook, too.

• Here’s a gorgeous ambient track from Dedekind Cut, an artist (and song) recommended in the Reddit thread I mentioned above.

• Lake Holden held a surprise this morning at dawn. Spot the moon. [LINK]

Choosing Your Input and Collaborating With Ghosts

I’m fascinated by Steven Soderbergh’s year-end Seen, Read list. The director’s started each new year since 2017 with a day-by-day record of everything he watched, read, and listened to in the previous year. Soderbergh recently unveiled 2019’s list, and it shows that he began the year watching a documentary on Area 51 and ended the year with an obscure ’40s film noir. And judging from everything in between, his media intake is constant and all over the place.

You may wonder how a busy film director and producer has all this leisure time. But is it leisure time? Here’s author and music critic Ted Gioia on the Conversations With Tyler podcast:

In your life, you will be evaluated on your output. Your boss will evaluate you on our output. If you’re a writer like me, the audience will evaluate you on your output. But your input is just as important. If you don’t have good input you cannot maintain good output… I know for a fact I could not do what I do if I was not zealous in managing high quality inputs into my mind every day of my life… This is the reason why I’m able to do this, because I have constant, good quality input, that is the only reason why I can maintain the output.

If you work in a creative field, then you need to have a firehose of input. And that input will directly influence and guide your output. The input isn’t material to copy but is there to provide steady inspiration, affecting creativity’s mental space.

Steven Soderbergh’s media diet is unguided and seemingly unfocused, which opens him to surprises and unexpected creative inspirations. And, in response, his output jumps around genres and styles. There’s not a typical Soderbergh film though there are common threads and themes.

One can also guide the input to focus the output. I remember reading an interview years ago with Robert Smith of The Cure about his creative process. He explained that before recording an album, he selects a playlist of songs that conveys the mood he’s hoping to capture. Then he listens to nothing else but these songs for the entire time that he’s working on the record. That helps him maintain the mindset he’s after, shaping the tone of the album. This practice might be dangerous now that inspiration’s sometimes interpreted as theft, but I believe it’s a great idea to lay these creative foundations. Artists are always collaborating with ghosts, after all. It’s good to curate which ones you let through the door.

🔗→ Seen, Read 2019

🔗→ Ted Gioia on Music as Cultural Cloud Storage (Ep. 79)

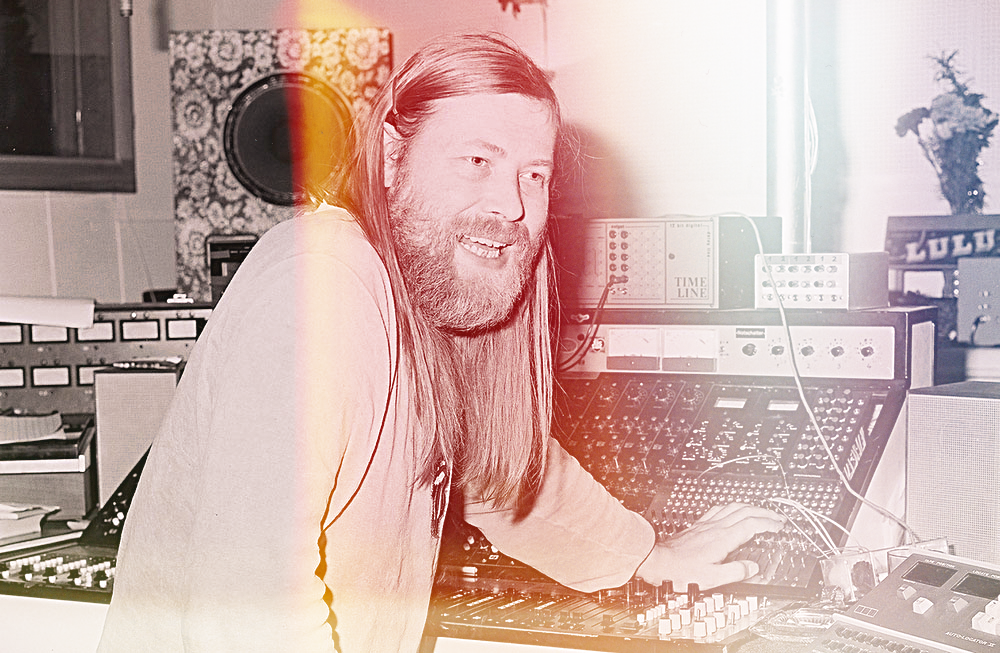

Conny Plank: The Potential of Noise, a Son’s Tribute

The documentary Conny Plank: The Potential Of Noise was more touching than I expected. The film is a collaboration of director Reto Caduff and Stephan Plank, Conny’s son. Stephan drives the documentary as conversations with musicians who worked with Conny Plank help him understand and rediscover his father.

Conny Plank died of cancer at 47 when Stephan was just 13. A lot of Stephan’s memories of his father revolve around these odd musicians who stayed and worked at the farmhouse studio. Often the musicians would join the family for dinner (indulgently prepared by Stephan’s mother Christa), and they would become Stephan’s temporary playmates in between sessions. So, in this documentary, Stephan is meeting people who not only have perspectives on his father but are also part of shadowy childhood memories. The musicians are also taken aback — the last time they saw Stephan he was a child and an oblivious studio mascot.

The highlight of the documentary is Stephan’s meeting with the classic rap duo Whodini. Did you remember that Conny Plank produced part of Whodini’s first album? I forgot, too, until this film pleasantly reminded me. Whodini was an upstart act in their late teens, suddenly flown to a farmhouse in rural Germany in a bold choice by their label. The duo grew to love the eccentric but brilliant Conny Plank, and this love and respect pour out of their interview segment. Stephan is visibly emotional as he hears another warm story of the universal impact and guiding influence of his father. Even I choked up a little.

There’s so much more in this film, including interviews with Michael Rother (Neu! and — early on — Kraftwerk guitarist), Eurythmics’ Dave Stewart (who may have been the last to work with Plank), and Holger Czukay (Can). Czukay comes off as kind of a jerk in his honesty about how Conny cared more about his studio than his relationship with his young son. It seems that Stephan has come to terms with this.

Noticeably absent is Brian Eno who stepped into Plank’s studio on more than one occasion. A section on the recording of Devo’s first album allows Eno most of his screen time, and that’s given to Gerald Casale talking about how he didn’t like Eno’s attempt to add his ‘pretty’ vocals and synth lines throughout the record.

Conny Plank: The Potential Of Noise is inspiring and a stirring tribute to a person who lived the creative life. But most of all it’s the story of a son finding his talented but distant father. With Father’s Day approaching, I can’t think of a better movie to watch, especially for those of us missing our dads.

Conny Plank: The Potential Of Noise currently streaming on Amazon Prime and available as a ‘rental’ on other services. And here’s a fine interview with Stephan Plank about the documentary. For what it’s worth, I’m pretty sure the no-show Stephan refers in that piece is Eno, not Bono.

Netflix and the Future of Award-Winning Indies

{Steven Spielberg’s} Academy Award attention is now devoted to ensuring that the race never sees another “Roma” — a Netflix film backed by massive sums, that didn’t play by the same rules as its analog-studio competitors. {…} As far as he’s concerned, as it currently stands Netflix should only compete for awards in the Emmy arena … {…}

“There’s a growing sense that if [Netflix] is going to behave like a studio, there should be some sort of standard,” said one Academy governor. “The rules were put into effect when no one could conceive of this present or this future. We need a little clarity.”

The landscape is changing so fast for film, and Spielberg and company should be advised to tread lightly. I understand the need for guidelines but what separates a ‘TV show’ from a ‘feature film’ is probably the wrong question and one we may not need to ask in several years. That separation, more and more, is about the budget — with superhero and ‘event’ films dominating the cineplexes while daring directors have no choice but to turn to the streaming studios.

And who can blame them? The number of people that saw Roma vs. its audience if it had a traditional theater release is unarguably exponential. And a common complaint about Oscar fare is that not enough people have seen these films, or can see these films as they are often in limited (or arthouse) runs. Now more people are watching great movies. I don’t understand how Spielberg sees this as a bad thing. Or, even if he does — my guess (and hope) is his opposition is overblown, that he’s exploring guidelines that reflect a changing industry. After all, I can’t imagine he’d want to rebuff Martin Scorsese, whose next film is a Netflix joint.

I personally feel we’re entering a golden age for independent film. But that golden age will primarily exist on our televisions.

Also, in the Indiewire piece, there’s a list of reasons why Netflix supposedly has an unfair advantage. This one caught my eye:

Netflix spent too much. One Oscar strategist estimated “Roma” at $50 million in Oscar spend, with “Green Book” at $5 million.

Ultimately, awards are nonsense though I understand the marketing benefits, role in legacy-setting, and prestige. But at least we should keep some veneer of the ‘best film’ as the winner of Best Film. If an out-of-control marketing budget for an Oscar campaign is an unfair advantage, then I feel the problem lies within the Academy and the voting process.

Insert comment about parallels with the screwed-up state of US democracy here.

🔗→ The Spielberg vs. Netflix Battle Could Mean Collateral Damage for Indies at the Oscars

Delving Into HyperNormalisation

Acclaimed documentarian Adam Curtis is at it again with HyperNormalisation, another stab at explaining the many forces responsible for the confounding state of our present world. Hyperallergic has a fascinating analysis of Curtis’s latest project and pulls this frightening / enlightening quote from the documentary’s narration:

The liberals were outraged by Trump, but they expressed their anger in cyberspace — so it had no effect. The algorithms made sure it only spoke to people who already agreed with them. Instead, ironically, their waves of angry messages and tweets benefited the large corporations who ran the social media platforms. As one analyst put it, ‘angry people click more.’ It meant that the radical fury that came like waves across the Internet no longer had the power to change the world.

Going a bit off path (if you’ll indulge me, as this is primarily a music biz blog), we can also read this as a warning against putting all of one’s promotional efforts into social media. There are indeed many potential listeners to reach through, say, Facebook but there are limits. And those limits – determined by an algorithm you can’t control, and reaching into a bubble of the already converted – won’t give your project much expansion outside of your current circle. It’s low hanging fruit in the short term as you’re hitting those who are into ‘similar music’ (at least those that pay attention to Facebook), but once that’s exhausted there’s nowhere to go, at least organically. Your own site and outside promotional efforts should always be a focus, with social media simply a tool to point the way. Treat social media like another – albeit quite effective – form of newsletter, instead applying the bulk of your energy where it matters and potentially affecting more people.

But I digress. HyperNormalisation is fantastic though IMO not as masterful (or convincing) as 2015’s Bitter Lake. But that’s a high bar, and HyperNormalisation is effective and affecting, with many brilliant examples of Curtis’s hallmark montages and expert music selections working in tandem to wordlessly implant his message. I watched it before the presidential election and its themes continue to haunt (and scar) my thoughts afterwards. If you’re in the UK you can view HyperNormalisation now on the BBC iPlayer. If you’re not, have a look on YouTube and you might just see it pop up now and again.

Artspace recently interviewed Adam Curtis, focusing on HyperNormalisation‘s assertion that a rise in individualism (epitomized in the film by Patti Smith and the ’70s NYC art scene) created an un-unified weakness in liberal movements.

{Curtis:} We look back at past ages and see how things people deeply believed in at the time were actually a rigid conformity that prevented them from seeing important changes that were happening elsewhere. And I sometimes wonder whether the very idea of self-expression might be the rigid conformity of our age. It might be preventing us from seeing really radical and different ideas that are sitting out on the margins – different ideas about what real freedom is, that have little to do with our present day fetishization of the self. The problem with today’s art is that far from revealing those new ideas to us, it may be actually stopping us from seeing them.

This might be quite a difficult one to get over, but I think this is really important: however radical your message is as an artist, you are doing it through self-expression – the central dominant ideology of modern capitalism. And by doing that, you’re actually far from questioning the monster and pulling the monster down. You’re feeding the monster. Because the more people come to believe that self-expression is the end of everything, is the ultimate goal, the more the modern system of power becomes stronger, not weaker.

That whole Artspace interview is a mindfuck, as is pretty much Adam Curtis’s entire output. If this is new to you then prepare yourself for the rabbit hole.

The Prescience of Children of Men

For some reason (ugh), last night I decided to re-watch the fantastic and fantastically disturbing 2006 film Children of Men. According to a quick search of Twitter, I was not alone.

Children of Men is having a remarkable resurgence — not just because of its tenth anniversary but because of its unsettling relevance at the conclusion of this annus horribilis. There have been glowing reappraisals on grounds both sociopolitical and artistic. It’s getting the kind of online attention it sorely lacked ten years ago, generating recent headlines like “The Syrian Refugee Crisis Is Our Children of Men Moment” and “Are We Living in the Dawning of Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men?” As critic David Ehrlich put it in November, “Children of Men may be set in 2027,” but in 2016, “it suddenly became clear that its time had come.”

Children of Men imagines a fallen world, yes, but it also imagines a once-cynical person being reborn with purpose and clarity. It’s a story about how people like me, those who have the luxury of tuning out, need to awaken. This has been a brutal year, but we were already suffering from a kind of spiritual infertility: The old ideologies long ago stopped working. In a period where the philosophical pillars supporting the global left, right, and center are crumbling, the film’s desperate plea for the creation and protection of new ideas feels bracingly relevant.

Tons of spoilers in that Vulture article linked above, so don’t read it until you’ve watched the movie. Children of Men is presently streaming and rentable on various services.

Update: Here’s a fantastic ‘case study’ on Children of Men by The Nerdwriter: